Waste Disposal

Explore how the two most popular methods of waste disposal incineration and landfills work, their environmental impacts, and how cities decide between both systems.

How Landfills Work

Landfills look simple from the outside just large areas where waste is dumped and eventually covered. But in reality, a modern landfill is a tightly engineered system designed to isolate waste from the environment for decades or even centuries. Unlike incineration, which destroys waste through combustion, landfilling stores waste and lets nature take over through slow biological and chemical processes. In this lesson you’ll learn how a sanitary landfill is built, how waste behaves underground, what gases it produces, and why leachate management is one of the most important parts of the entire system.

How a Modern Landfill Is Engineered

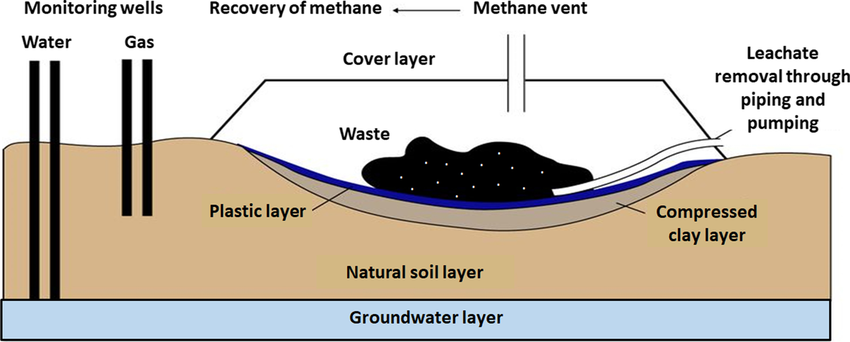

A landfill is not a just hole in the ground. It is a layered containment system designed to keep waste sealed off from surrounding soil, groundwater, and air. The entire structure is built like a sandwich of different barriers, with each layer performing a specific job.

At the foundation, you find a compacted clay layer or an engineered clay substitute. This clay barrier is chosen because it has extremely low permeability, meaning liquids cannot easily pass through it. Above the clay, a synthetic liner creates a second impermeable layer. These dual liners form the primary defense against waste leaking into groundwater.

Once the liners are installed, drainage layers are added on top. This usually includes gravel beds and perforated pipes that collect any liquid forming inside the landfill. Only after the liner and collection systems are in place can waste begin to be deposited on top of it. Even during active dumping, operators carefully layer and compact waste to reduce air pockets, limit movement, and stabilize the growing mass. Daily cover, usually soil, is placed on top of fresh waste at the end of each day to limit odor, pests, and debris being blown away by the wind.

The combination of clay, synthetic liners, drainage systems, and daily cover turns the landfill into a controlled environment rather than an uncontrolled dump.

What Happens to Waste Underground

Once buried, waste undergoes a slow transformation driven by biology, chemistry, heat, and pressure. At first, oxygen trapped in the waste supports aerobic decomposition, meaning microbes that need oxygen begin breaking down organic materials. This stage is short-lived because oxygen gets used up quickly in the compacted layers.

After oxygen is depleted, conditions shift to anaerobic decomposition. Anaerobic microbes take over, breaking down organic matter without oxygen. This process is far slower, but it is the dominant mechanism in a landfill. Instead of producing carbon dioxide alone, anaerobic decomposition generates methane, a gas formed when microbes digest organic waste in oxygen-free environments.

This underground environment is warm, humid, and constantly shifting. Waste settles unevenly over time, sometimes by meters. Paper and cardboard, despite being biodegradable on the surface, can persist for decades under landfill conditions because the system lacks the oxygen, sunlight, and microbial diversity needed for rapid breakdown.

Plastics, synthetic textiles, and many modern materials remain almost unchanged. They do not decompose in any meaningful timeframe. Metals corrode slowly, and glass remains inert. Because of this mix, decomposition in a landfill is not uniform. Pockets of waste may remain intact long after the surrounding material has decomposed.

Understanding these internal processes explains why landfills require monitoring long after they close. Decomposition slows down but never truly stops.

Methane Generation Inside a Landfill

Methane is a natural byproduct of anaerobic decomposition. In a landfill, methane forms continuously wherever organic material breaks down without oxygen. The gas accumulates in the void spaces within the waste and migrates upward or sideways until it can escape. Because methane is flammable and can form explosive concentrations, modern landfills install gas collection systems consisting of vertical wells and pipes that extract gas from the waste mass.

The gas is usually routed to one of three destinations:

- flaring (burning it off)

- energy recovery (using it as a fuel)

- or purification into pipeline-grade gas.

Landfill gas is typically around half methane and half carbon dioxide. Moisture, temperature, and the composition of waste all influence the rate of methane production. Organic-rich waste streams, such as food scraps and paper, generate more methane. Very dry landfills produce less gas but also slow decomposition, meaning their active life extends far longer.

Methane generation begins a few months after waste is buried, peaks after several years, and can continue for decades. This extended timeline is one of the defining characteristics of landfills as a disposal method.

How Leachate Forms and Why It Must Be Managed

Alongside methane, another byproduct forms underground: leachate. Leachate is a liquid created when water percolates through waste and absorbs dissolved chemicals, metals, organic compounds, and other contaminants. Rainwater is the main source, but moisture from the waste itself also contributes.

In an unmanaged landfill, leachate would seep into soil and groundwater, carrying pollutants far beyond the landfill site. Modern landfills prevent this through engineered drainage systems. Collected leachate is pumped out and sent to wastewater treatment plants, where it undergoes specialized treatment to remove contaminants. This process continues long after the landfill closes because leachate production can persist for decades as water slowly moves through buried waste.

Effective leachate management is the backbone of landfill environmental control. Without it, landfills would pose immediate and severe risks to groundwater.

Highlights

A modern landfill is a carefully engineered containment system designed to isolate waste from the environment. Inside, waste breaks down slowly without oxygen, generating methane and producing leachate that must be collected and treated. Compaction, daily cover, liners, and gas collection systems keep the process controlled.